A Lake Where the Rivers Have No Names

I'm being a bit nostalgic here.

The other night my 8 year-old daughter was watching a show where a father was telling his wife about a river he fished when he was young. I mentioned to her that I did the same thing when I was young in Alaska.

I told her that almost every weekend and holiday in the summer my father, brothers and I would fly to a lake to fish it and its rivers. She asked me the name of the rivers at the lake, and it hit me that I didn't know. Not only that, I'd never known. We always just referred to them as "the inlet,” "the outlet,” and other names of reference, such as "the river at the south end."

My dad had a 185 Cessna airplane on floats, and the large lake that we had a cabin on was unreachable by road. It would take about an hour to fly there. We'd pass the time in the airplane spotting sheep in the valley as we flew in, and gazing off at miles of uninhabited terrain as it drifted off beneath us.

There were other cabins at the lake, but because of the size and remoteness we usually didn't encounter other people. We'd throw our gear in the small cabin as fast as we could in the hope of getting in more fishing time before we would get tired and need to sleep on that first day.

We'd slide our boat out of the boatshed and into the water as a group, then the strongest man would wrap his arms around an Evinrude motor and carry it to the boat, trying his best to make it look like it wasn't a struggle. It was a rite of passage to young men wanting to impress their father and brothers. Initially, it was my dad that did this when we were young, but over the years it became my older brother, then the middle.

Being nearly ten years younger than my brothers, they would be in their 30’s and my father in his 50’s by the time it was my job. I was, of course, very proud to finally have that responsibility.

There are lots of potential obstacles to having a successful fishing trip. Health, weather, problems with fishing gear that is likely well beyond its life expectancy. By the time we’d loaded ourselves and the gear into the boat, there was one potential obstacle remaining.

The Evinrude motor was a reliable old fellow, but waking him out of a slumber could be an exhausting chore. I had many tense moments bobbing at the front of that boat watching my father and brothers take turns yanking at the pull cord, mumbling to themselves that maybe this was the time it finally wouldn’t start. After a few minutes and sometimes a few curses, it would finally jump to life, bringing back the excitement that had briefly left us.

The Squirrel War

Alaska in the 80s was a pretty wild place. I mean that literally, it was all pretty outdoor, smoky, nature wild. Some of the major roads in Anchorage were still unpaved. Bears and moose occasionally wandered into school playgrounds, causing sudden chaos. It wasn’t uncommon to spend an entire night without electricity because someone got drunk and fucked up an electrical pole with their car.

If this happened in the winter it meant you were either calling your friends to see who had electricity and a warm house, or you were getting the entire family together with blankets and sleeping together to generate some warmth. I have fond memories of our father starting a fire in the fireplace and getting us all together to sleep in front of it while we waited for the lights to suddenly pop on when the electrical issue was fixed.

I was a small child, and experiencing something like that, with my brothers and parents abruptly forced into this exciting situation where we were all together and enjoying each other's company, along with a slight sprinkle in my head of “we might die because it’s 30 below outside” made me love the thrill of it.

I secretly didn’t want the electricity to come back on. Unless we were going to die.

Anyway, back to the point of Alaska being wild. In those days it seemed like if there was an animal around, it was trying to kill you if you weren’t trying to kill it. It was just this constant circle of man slaying animals and animals slaying man up there. You heard about it in school, in the newspaper, on tv. It was everywhere.

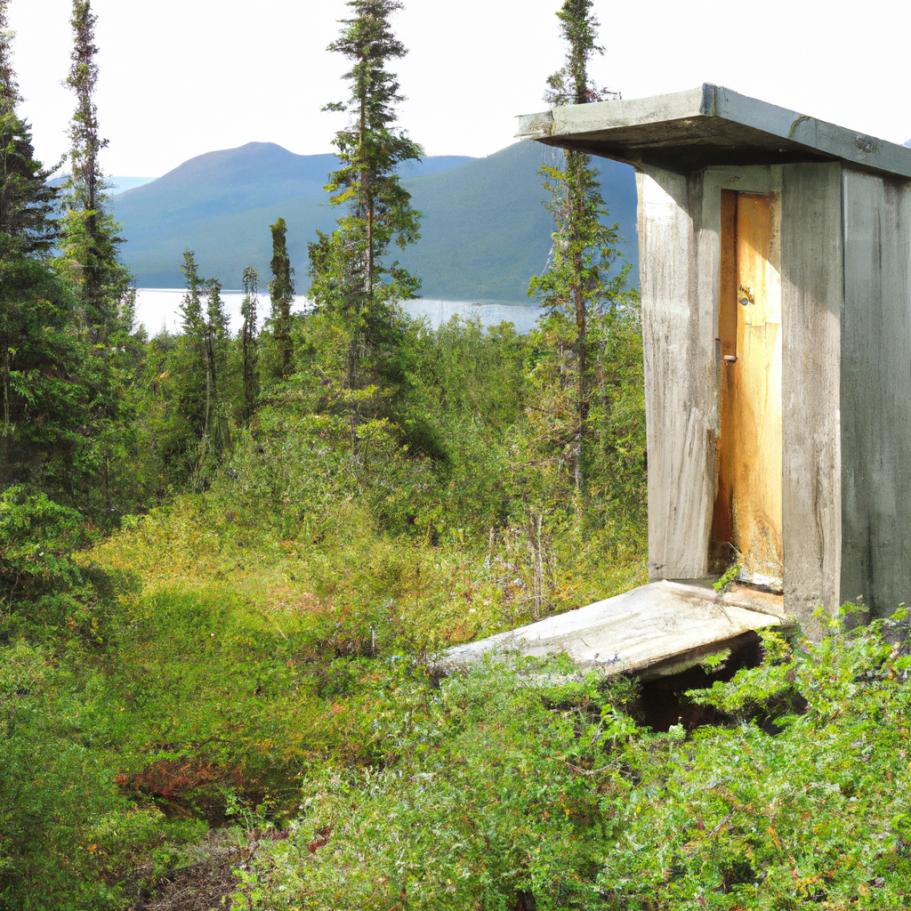

Our cabin at Crosswind Lake consisted of the main cabin, and a small outhouse positioned about 15 feet away from it. For some reason, squirrels loved to break into the outhouse, build nests, and create a big mess. I say “squirrels” plural because our father had become obsessed with eliminating any rodent that dared trespass in his precious outhouse.

He set traps in the outhouse. The squirrels kept dying, and new ones kept coming to take their place.

Any time we made a new visit to the cabin, after landing and beaching the airplane, practically before the propeller had stopped spinning, our father would leap out of the aircraft and book it for that damn outhouse, leaving three young boys to fend for themselves with a massive aircraft delicately grasping at the rocky shore of the lake.

It was very easy to know the results of his small trapping endeavors. There were three possible audible alerts that we would hear at this point, while we held to the lines of that plane, doing our best to keep it ashore.

Silence meant that all was good and no squirrel had dared penetrate his outhouse defenses. Curses and the sound of wood and objects being slammed meant that a squirrel, skilled in the ways of the ninja, had somehow successfully eluded his defenses and ransacked the place. Finally, outrageous shouts of victory and blood feuds laid to rest meant that a squirrel had been caught in his trap and found the early death that it deserved.

In all the time that we’d visited that cabin with our father we never saw a live squirrel get killed. They were always dead by the time we arrived. It was unheard of. Almost as unheard of as our mother visiting the cabin with us.

Sometimes in life the stars align and the most ridiculous of situations occur, causing such absolute chaos that it boggles your little 5 year-old brain.

Sometime around the summer of 1980, as we prepared for a trip to the cabin with our father, word spread amongst the brothers that our mother was going to join us. There was disbelief, awe, amazement. This never happened. It was more believable that the pope himself would join us on a trip to the cabin.

Our mother is a beautiful Bolivian woman who preferred more of the comforts of home over those of the wilderness. She liked electricity, running water, flushable toilets, and being able to shower daily. She did not like the cabin. Most of all, she didn’t like the idea of animals suffering. Even fish being hurt bothered her.

Sure enough, mom flew with us to the cabin. My brothers and I were excited like we were shot out of a cannon. Having both our parents there was going to be magical. Even though mom was going to stay in the cabin while we went out in the boat to fish, we loved the idea of her being there with us for the morning and evening when we were inside and not fishing.

There had been no squirrel in our father's traps when we arrived, so, as usual, the traps were left set, open and ready in the shelves of the outhouse, safely away from any of us accidentally triggering them.

It was sometime around midmorning on the second day, when all of us were finishing up our breakfast in the cabin that we heard outside a snap, a scuffle, and the distinct sound of an animal scurrying across wood.

All of us were sitting at the cabin table, so there was understandable confusion about what was making the noise outside. Our father knew immediately. He opened the front door of that cabin and whipped around the corner faster than I’ve ever seen a man move since.

The rest of us, three young boys and a mother, ran to the kitchen where there was a small window looking in the direction of the outhouse. To our horror, a squirrel had not only been caught in our father's trap, pinning his rear legs in the device, but it was now crawling through the open outhouse door and across the outside wall of the structure, towing this metal contraption behind it.

Mom screamed. My brothers and I were in too much shock to say anything.

I think in many of our minds, and perhaps our mother's too, we expected dad to free the creature out of mercy. To set it free so it could heal and warn all other squirrels in the vicinity that nobody messes with the outhouse of the cabin with the green roof.

Instead, when our father soon appeared into view of that small window we were all looking through, our eyes the size of dinner plates, he was carrying a piece of wood so large that it looked better intended to slay rabid brown bears than little squirrels.

If the intensity of squirrel beatings was kept record of in the Copper River Census Area of Alaska this had to be in the top 10.

I’m sure the poor fellow was dead within seconds, but the sound of the muffled flesh being pounded into a pulp against a wooden outhouse still echoes in my soul.

The silence that followed was almost worse. While my brothers and I continued to gaze out that window in shock, urging our young minds to make sense of what we just witnessed, our mother finally mumbled a few words in Spanish. Then a few more, a little louder. It progressed from there.

To modify a quote from George Costanza, the Latina was angry that day, my friends. The next few hours were like something out of a Hollywood thriller.

In the end, things settled down and peace was made. Our parents were never physical with us, nor each other, so discussions were had and agreements were made that night. Mom would never again join us on a trip to the cabin, and our father would never again ask her to.

The Inlet and the Outlet

The two rivers we fished most at Crosswind were the inlet and the outlet. They were both located at the northern side of the lake, the inlet being more to the west.

The fishing holes of the inlet were dark as ink and they rarely revealed their secrets. If you threw your fly in the water you wouldn’t know if there was a fish beneath until it had taken your lure.

The outlet, in contrast, was crystal clear. You could walk its shores and see the fish so distinctly that you could identify the species.

They felt like two rivers that had no right to be attached to the same lake, but there they were, almost magical in their abrupt contrast.

Grayling were the preferred prey. They were darker in color and in number than the whitefish that they mingled with. They were also less easily coaxed out of their place. To get one to take your fly you had to be patient and precise. Two qualities that are in short supply when you are a young boy.

Nothing makes a little brother more anxious than seeing his big brother achieve something in a competition before he does. Inevitably, one of my brothers would hook a juicy grayling, pull it to the shore and hoist it up for the others to see. I would feign a grin and quietly curse my fly for being an inadequate piece of shit, clearly not attractive enough to get the attention of even the most stupid fish.

There are things that you do in life that get harder to do correctly the more deliberate you are about them. Things like dancing, eating with chopsticks, taking a reluctant poop, and fly fishing. You cannot hurry the process with these things, and if you try to it will end poorly.

After a few minutes wasted snagging a tree, or casting my fly too far and catching the other side of the river, I would eventually settle down. Like the nearby grass stirring in the breeze, I would catch a rhythm, swing my arms back and forth as I extended my line, then drop my fly where it wanted to be.

The fish would always take the bait soon after. I just had to stop trying so hard.

The dark waters would come into the lake through the inlet and the clean waters would leave through the outlet. A breath is taken in, a breath is let out. A child releases its first shrill cry, an old man takes a final shallow breath.

A father cannot always keep an eye on his youngest child, especially when he is prone to curious and reckless behavior. A fly is dropped on the surface of the river and an eager fish takes the bait, never to again be what it was before.

When I was in my twenties I returned to the lake with my father. It was just the two of us, which was very rare. I’m not sure that we had ever done it before. We didn’t know it would be the last time we visited the lake, or perhaps we did, but didn’t want to look directly into that possibility.

We were in the middle of Crosswind and the weather was miserable. It had been raining on us for hours as we sat in that boat, trolling the favorite spot for lake trout. We hadn’t caught anything the whole day.

I normally knew better than to complain, but I was an adult, and no longer did my father discipline me for speaking my mind about thoughts that were better kept unsaid. I was soaked, I was cold and I was carrying a wound that had been with me for years. I finally told him the whole day was miserable and I hated it.

A good father can tell when there’s more behind a child’s words than those that are spoken.

When I was young such disrespect would have been dealt with quickly, a sharp glance in my direction usually enough to end the matter. Instead, this time my father looked at me with a kindness that he never would have shown before his cancer fight.

He told me that all the pain and misery we feel is important, and it shouldn’t be rejected and ignored, because without it we wouldn't realize how great the wonderful things in life can feel, both physical and emotional.

As he spoke to me his back was to the north side of the lake. In the horizon, the inlet over his right shoulder, the outlet over his left.

It was one of the few times I saw him really open up and speak from his heart. His words comforted me, and I said no more, because nothing more needed to be said. We settled in with our fishing poles as we continued to drift across the lake.

My father would die from that same cancer ten years later, after we thought he had beaten it. He lived long enough to know and love my son, and I am thankful for that.

I feel as though I had two fathers. One from the inlet, and then one from the outlet. They both loved me and they both taught me their lessons about life.

The last time you do something in life can be very emotional, not when it happens, but when you later realize it has passed.

The last time you visited a family cabin before it was sold away. The last time you picked up a child before they no longer needed your help. The last time you spoke with a parent before they passed away. The last time you caught a fish in a lake where time stood still and dark waters were cleansed to clear.

A picture of my father, Jim, at Crosswind Lake

Necesitamos su consentimiento para cargar las traducciones

Utilizamos un servicio de terceros para traducir el contenido del sitio web que puede recopilar datos sobre su actividad. Por favor revise los detalles en la política de privacidad y acepte el servicio para ver las traducciones.